I’ve always looked at reading a book like a conversation between author and reader. Through reading, you have the golden opportunity of communicating with people that are separated from you by time and space.

However, I didn’t realize the truth of this statement in my actions. As a young teenager, I read a lot of classic fiction. I would speed-read the chapters, sigh at the end, and leave unchanged.

Thinking back, I wonder: was it the books I was reading that didn’t change me, or was it my attitude toward the reading process? Even fiction books have deep underlying philosophical issues they address. Was I doing justice to the books I read by simply reading them and putting them away?

Absolutely not. And if that’s how you read, your philosophy on information consumption is all wrong. A good book is not there for you to scan and place back on the shelf. It stands as an invitation to dialogue with a great conversationalist.

How then do you invest in the conversation? A good dialogue always includes more than “Hey, how are you? The weather’s great.” Is there a way to take your communication with book authors to a deeper level? I didn’t know the answer to this until I read Mortimer Adler’s essay How to Mark a Book. The principle behind his idea is one does not own a book until he has gotten the words into his bloodstream.

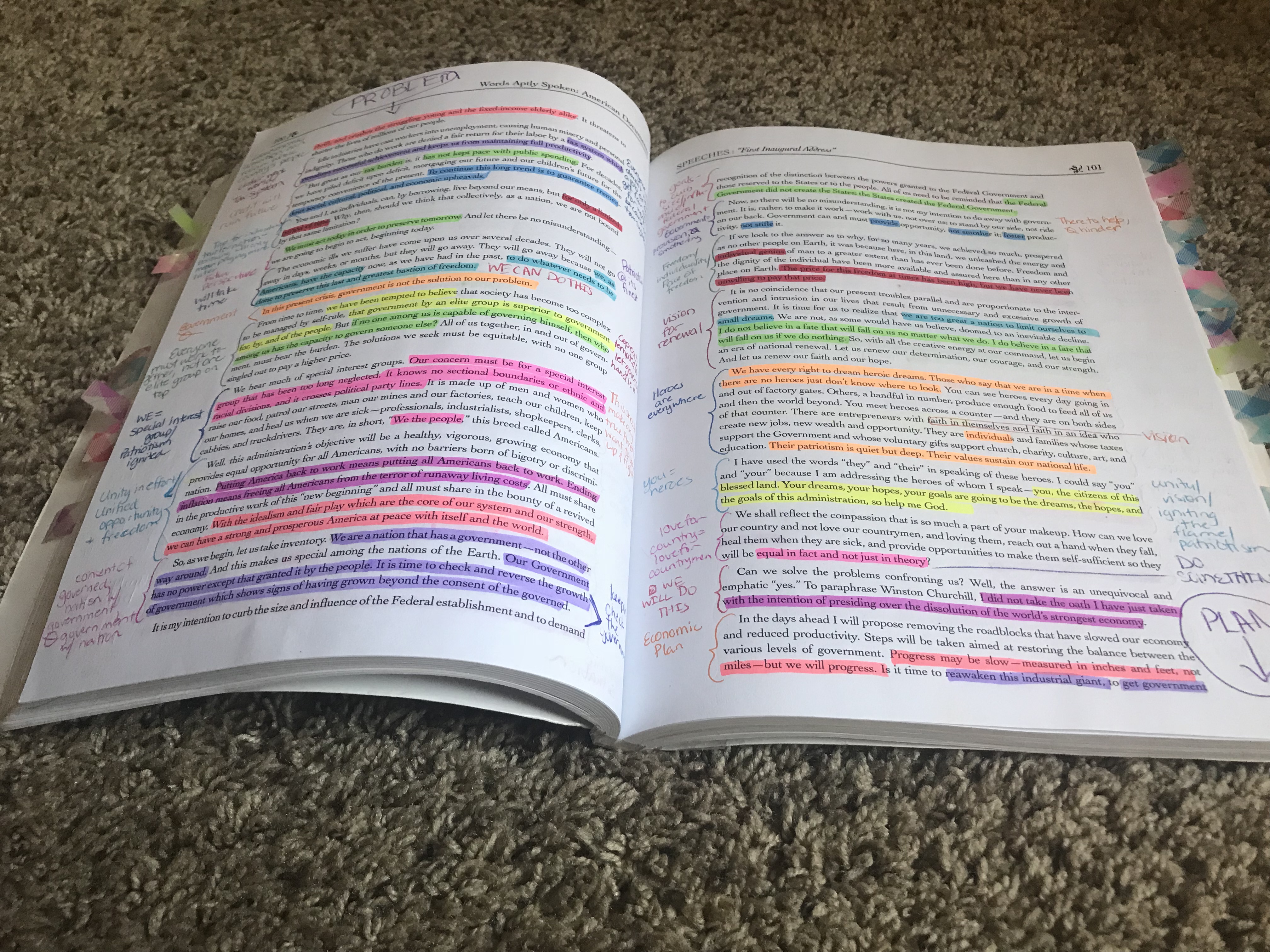

“There are three kinds of book owners. The first has all the standard sets and best sellers — unread, untouched. (This deluded individual owns woodpulp and ink, not books.) The second has a great many books — a few of them read through, most of them dipped into, but all of them as clean and shiny as the day they were bought. (This person would probably like to make books his own, but is restrained by a false respect for their physical appearance.) The third has a few books or many — every one of them dog-eared and dilapidated, shaken and loosened by continual use, marked and scribbled in from front to back. (This man owns books.)” -Mortimer Adler, How to Mark a Book

Until you know the “soul” of a book, you do not own it. Until you have grappled with the ideas in your mind, debated the author’s points one by one, and challenged the boxes of thinking you built, you have no idea what a book is truly worth.

What makes a “good” book? Millions of people have written; what separates the excellent reading material from that of poor quality? This differentiation can also be found in the soul of the book. Because books are reflections of the souls of their authors, they begin to take on characteristics that are human-like. If a book at its core is rich, deep, and beautiful, it will challenge the reader constantly and urge him to grow and thrive. Conversely, if the book fails to challenge the reader, or propels him toward negativity and chaos, its soul probably has little quality and is not worth pursuing to a deep level.

But when you have found a good book, do not let its core elements rot away on your bookshelf. Read it; write in it; interact with the author through his words.

“And that is exactly what reading a book should be: a conversation between you and the author. Presumably he knows more about the subject than you do; naturally, you’ll have the proper humility as you approach him. But don’t let anybody tell you that a reader is supposed to be solely on the receiving end. Understanding is a two-way operation; learning doesn’t consist in being an empty receptacle. The learner has to question himself and question the teacher. He even has to argue with the teacher, once he understands what the teacher is saying. And marking a book is literally an expression of differences, or agreements of opinion, with the author.” -Mortimer Adler, How to Mark a Book

How do you mark a book? Use tabs to mark special places. Highlight the quotes that speak to you. Don’t be afraid to write a note of your questions and ideas about the author’s points. Use the front and back covers to write outlines of the book. Through marking a book, you will make it yours!

I have learned not to judge a library by the books whose glossy covers shine when the light hits them. Instead, I look for the dog-eared works that can hardly be read by anyone other than the owner. For these books tell the breathtaking story of the connection between an individual and an idea.